Homes for Change Housing Cooperative Ltd. and Work for Change Ltd. have developed one of the flagship schemes of the redevelopment of Hulme, a district which until a few years ago was one of the largest deck access estates in Europe.

Homes for Change has worked on the basis of seeing the local community as a strength rather than a problem. It has sought to embrace rather than suppress the alternative lifestyles and open tolerant community that have characterised Hulme at its best. It demonstrates how much can be achieved by community control and is probably the most significant community initiated development in Manchester for many years.

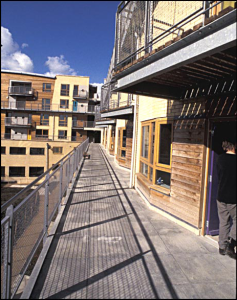

The relevance of the Homes for Change model is not so much the architecture of the buildings, striking as this is, but the process by which it was created. It illustrates that when local people are given a full and informed choice over their environment, the result need not be the blandness which has characterised so much ‘community architecture’.

Homes and Work for Change emerged from Hulme in 1987 as the Warehouse Project, a co-operative set up to claim one of the threatened city centre buildings as a mixed use development of residential and business units.

The 1988 Housing Act, subsequent moving goalposts and the escalating costs of refurbishment rendered a scheme to convert the city’s first police station unviable. The co-operative relocated its activities back to Hulme, bruised after 4 years work, but with a huge amount of experience, an unused allocation of grant funding and, crucially registration with the Housing Corporation (the UK Government’s social housing agency), something which few groups have achieved since 1988.

When it was announced that Hulme was to be redeveloped through the government sponsored City Challenge programme, Homes for Change was able to turn its attention to its home territory as an established co-operative and recognised Registered Social Landlord.

Whilst the Hulme built in the 1960’s may have failed, it nevertheless nurtured a strong if unconventional community. Because of its proximity to the universities in Manchester Hulme was an area of contrasts, 35% of the population had no qualifications at all whilst 25% had degrees or diplomas.

A stable community born and raised in the area lived alongside another population who would not have found housing elsewhere many of whom made the area their home. Its reputation for a strong, tolerant and open community attracted many different groups of people from a Jesuit group to an expressive gay community.

Hulme tenants were drawn from virtually all of the ethnic groups in Europe both indigenous and immigrant. It is important to balance the PR, for many in this community quite liked elements of the old Hulme, the proximity to the city centre, the size of the flats – big enough to set up small businesses, the tolerance of local people and the close networks of neighbours which developed on many of the walkways.

With the launch of the Government funded redevelopment of Hulme through a scheme called City Challenge, Homes for Change was conceived as a lifeboat to preserve a small part of the local community, not catered for elsewhere in the re-development.

The co-op sought not to reject the past but to build upon it by rescuing the best points of the old estate.

At the same time they used their very practical experience of its failings to ensure that these were not repeated in the new development. In doing this the co-operative has created a potential model for the regeneration of British cities and an alternative to the creeping suburbia which is colonising not only the countryside but also the very heart of our urban areas.

Homes for Change was accepted as one of the social housing developers in Hulme and following lengthy negotiations was allocated funding for 75 flats and a site in the heart of the area.

However the Housing Corporation had already decided that all new housing in Hulme was to be developed by 2 of the country’s largest housing associations, North British Housing Association and the Guinness Trust.

So the Guinness Trust was selected as the groups development partner. Under the terms of the partnership agreement Guinness was to undertake the development for the co-op whilst co-op members were given the right to be involved in decisions and to take on ownership on completion if they could raise the necessary finance.

This arrangement has led to inevitable tensions especially as phase 1 was dogged by contractual problems. However to Guinness’s credit, the fact that the building is radically different to anything that a mainstream housing association would have developed is testament to their commitment to see it through.